Our Rich Heritage

Read the original article by Mike Dow that appeared in Power Pickin' throughout this page below

Though musicians had been gathering to play music at the Denver Folklore Center since the early ‘60s–and the local scene even boasted a few local bands like Denver Grass–bluegrass remained largely unknown on the Front Range in the early ‘70s. So in ‘72, as a means of communicating with fellow bluegrass musicians and fans, a group of young pickers organized the Colorado Bluegrass Music Society. Founding CBMS member David Little recalls, “our only decision was to not have a festival, because they're work.”

Big Mon

At the time, multi-day bluegrass festivals were still young, the first one originating in Fincastle, VA in ‘65. But by ’73 there were nearly 70 such festivals around the country, and the Father of Bluegrass, Bill Monroe, wanted his own-and he wanted it in Colorado.

When members of CBMS met "Big Mon" after a show at Boulder’s Tulagi’s in ‘72, Monroe was determined to join forces with the Society to produce a Colorado festival. Monroe would book the national talent, and CBMS would organize and market the event. Monroe even offered to shoulder the Society’s financial burden by personally guaranteeing money to the bands and venue. Recalls David Little: "There wasn't any pressure. Monroe had said you won't lose anything.”

CBMS History

Thanks to Mike Dow for this updated summary of CBMS history which originally appeared in Pow’r Pick’n-date unkown. Below is the original article. Read the full article here:

https://bluegrass.com/rockygrass/festival-info/the-monroe-festivals

I want first off to thank Don, Sara and Georgia Watson for not only getting me the material (which will be turned over to the Society for their archives and the future enjoyment of its members) but also for saving the material all these many years. Some of it is in mint condition and it all has been helpful in writing this article (and possibly future ones) about CBMS’ role in starting and continuing the Rocky Mountain Bluegrass Festival before it was sold to Planet Bluegrass.

According to Dave Little, a founding member of CBMS, the Society began in the Fall of 1972 and one of its stated intentions was to NOT have a bluegrass festival but simply to promote bluegrass music in Colorado and the Rocky Mountain Region and coordinate the jamming for the enjoyment of its members. But when Bill Monroe brought his band to Tulagi’s in Boulder for an extended engagement and some of those early Society members, naturally, went to hear the Blue Grass Boys and meet the Big Mon, it wasn’t long before Bill had those pioneer Society members convinced to join forces and put on a festival in the following year.

1st Annual Rocky Mountain Bluegrass Festival

With less than six months to prepare, CBMS made arrangements to rent the Adams County Fairgrounds in Henderson. Music would be presented in the rodeo arena (with Charles Sawtelle running sound), and camping was available nearby. As plans progressed, Monroe made a special trip to Colorado to coach CBMS members on marketing and publicity. "He taught us what to do. And it worked. We had a big crowd," remembers Little. An estimated 6,500 people attended the 1st Annual Rocky Mountain Bluegrass Festival. The first four years of the festival earned a total profit of more than $20,000.The early lineups boasted major national talent including Lester Flatt, Ralph Stanley, and Jim & Jesse. But the highlight was Big Mon himself. “He'd park the Bluegrass Express someplace where people knew where he was,” recalls Little. “He liked to be seen and to talk to people. And he'd play a lot with people.“ Also, we were reminded that you don‘t dance during the gospel numbers,” remembers CBMS board member George Watson.

The festival continued at Adams County Fairgrounds under the leadership of CBMS. Musician and radio personality Jerry Mills recalls the impact of the festival: “The legends loved coming to Colorado. In their suits and ties, they’d brush the dust off from the fairgrounds and put on great shows. For a lot of us younger pickers, it was a good model to follow.”

Hot Lineups

Monroe ended his involvement with the festival in ‘77, but those early festivals achieved their goal of raising the profile of bluegrass music in Colorado. The Thursday night jams at Ralph’s Top Shop began in ’75; KGNU’s Old Grass Gnu Grass went on the air in ’78; Swallow Hill was founded in ’79.

Colorado began to produce national bluegrass bands, most significantly: Hot Rize. Debuting at the festival in ’79, the Boulder quartet became the festival’s “host band” in the mid-‘80s, appearing 10 times before officially disbanding in ‘90. Another Colorado band, Left Hand String Band, began an eight-year festival run in ’83, only slowing down when band members, led by Drew Emmitt, formed Leftover Salmon in ’89.

Band and instrument contests were an integral part of the festival from the beginning. Banjo player Dennis Bailey smiles when recalling the judge recruitment process: “Some official would be asking random attendees, ‘Do you know anything about music? You don't? Great! Would you like to judge the banjo contest?’"

Booked by CBMS, the festival lineups remained strong, balancing local talent with national acts, including memorable performances by Tony Rice, Doyle Lawson, and Seldom Scene. But the Adams County location was not without its shortcomings, including noise from overhead jets en route to Stapleton, and dust. CBMS board member Mike Dow recalls: “There was nothing but dirt and the western winds to blow the dust into the crowd.”

With rising production costs in Adams County, CBMS moved the festival to Loveland’s Larimer County Fairgrounds in ‘88, to coincide with the Loveland Corn Roast. While the Corn Roast attracted large crowds on Saturday, Friday, and Sunday proved problematic. Dow remembers the ’88 festival: “By the end of Sunday afternoon, the Virginia Squires were finishing up their set and they invited most of the audience up on stage to close the festival with them.“

The festival continued in Loveland for years before Corn Roast organizers decided to book their own entertainment. The 20th annual festival was without a home.

Photos courtesy of Kevin Slick

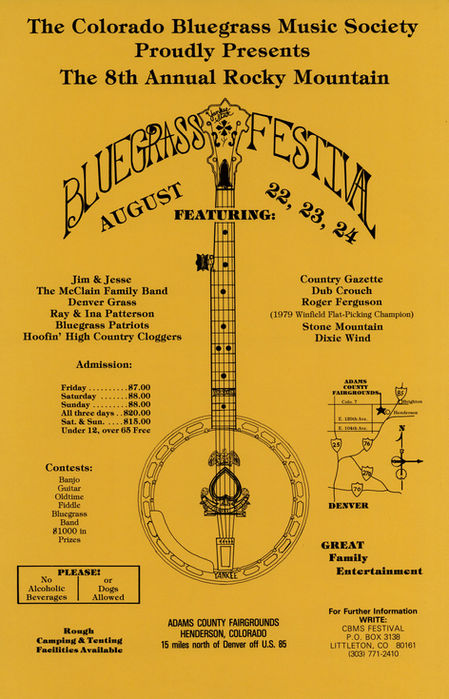

Colorado Rocky Mountain Bluegrass Festival Posters

1973 - 1980

Courtesy of Kevin Slick

Festival becomes RockyGrass!

The headline of June ‘92’s issue of CBMS newsletter Pow’r Pick’n read: “20th Annual Rocky Mountain Bluegrass Festival Moved to L_____!” After a failed attempt to relocate to Winter Park, CBMS approached the organizers of the Telluride Bluegrass Festival (the future Planet Bluegrass) to help find a new site for the festival. With less than three months until the festival’s 20th anniversary, the site had not yet been chosen between Lake Eldora or a property in Lyons owned by the Center for Wildflower Preservation.

Planet Bluegrass vice-president Steve Szymanski recounts their early motives: “I thought it was really a non-profit venture. We were going to assist and have a nice musical experience and cool community thing.”

Ultimately, the Lyons property won out. Within two months, Planet Bluegrass would negotiate a deal with the Town of Lyons, prepare the property for a festival, and book a 20th anniversary lineup that would ultimately include Alison Krauss & Union Station and Tony Rice and Norman Blake.

Though some CBMS members were frustrated by new policies– notably, paid parking and higher camping fees–the festival was generally considered a success. "Let's face it, folks, rodeo grounds are for horses; and mountains, trees, and rivers are for bluegrassers!" wrote CBMS member Jeff Jeros.

Planet Bluegrass lost $7,000 that first year. "We're not going to do this as volunteers,” said Planet Bluegrass president Craig Ferguson. “If we're going to do this and get involved, then we're going to take it over.” Ultimately, CBMS agreed to sell the festival for $10,000. And the festival’s momentum began anew.

Over the next few years, the name informally changed to RockyGrass –a name better suiting Planet Bluegrass’s style. Recordings from the third year in Lyons were released as theRockyGrass Live CD, and by ‘95 Planet Bluegrass had relocated its bluegrass academy from Telluride to Lyons. The festival’s once uncertain fate was now safe in its new home on the Planet Bluegrass Ranch. “In many ways, RockyGrass became the soul of Planet Bluegrass,” says Ferguson.

“I remember giggling,” says Szymanski of the first single-day sellout in ’98. Yet within a few years, the entire festival was reliably selling-out in advance, with demand for onsite camping and Academy classes crippling the entire Lyons phone system when those went on sale in December.

“More than any of our events it's the community experience as a catalyst,” says Szymanski. This community spirit is manifest among the musicians: David Grisman and Dan Tyminski stepping forward in 2010 to help the festival fill-in for an injured Tony Rice; Sam Bush bringing his only-at-RockyGrass “Bluegrass Band.”

And this community experience is manifest among festivarians: enduring the infamous “Soggygrass” of ’04; hanging in there with the overly-progressive-Saturday of ’08; and continuing to create the country’s most open and virtuosic campground pickin’ circles. “You can stand in line for an ice cream and have a really intelligent conversation about bluegrass and banjo solos and tone rings,” laughs musician KC Groves.

Special thanks to Mike Dow and David Little.

20th Annual Colorado Rocky Mountain Bluegrass FestivalAugust 7-9, 1992. (First year in Lyons, CO)

Tony Rice & Norman Blake • Alison Krauss & Union Station • Tim O’Brien & The Frequent Fliers • Tony Rice Unit • New Tradition • Charles Sawtelle & The Whippets • Left Hand String Band • Pete & Joan Wernick • Norman & Nancy Blake • Quickdraw • Bluegrass Patriots • Tim & Mollie O’Brien • Southern Exposure

RockyGrass remains unique in the bluegrass world for its single main stage and policy of limiting bands to a single set. Where many festivals now aspire toward a “big tent” musical philosophy, RockyGrass remains focused on traditional bluegrass even as its audience grows more musically progressive.

So what would Monroe think of the 40th Anniversary of his Colorado festival? Ferguson reasons: “Some of the music he might not like, but he'd sure want to play it. Bill loved to play for a crowd. And I know he'd love the RockyGrass audience.”

.jpg)